On the Case

On the Case

By Lyle Suh, BS; Ajit S. Puri, MD; and Anna Luisa Kuhn, MD, PhD

Radiology Today

Vol. 25 No. 4 P. 30

History

A 21-year-old woman with a history of sickle cell disease, right middle cerebral artery (MCA) stroke at the age of 12 with residual left hemiparesis, and chronic right internal carotid artery (ICA) occlusion presented for evaluation of severe headaches. Cross-section imaging of the brain with MRI was performed and the neurointerventional service was consulted.

Findings

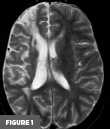

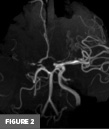

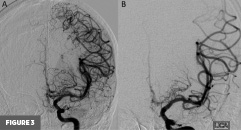

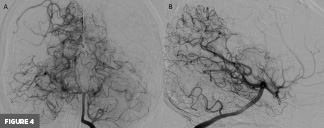

Axial T2-weighted MR image at the level of the basal ganglia demonstrated right frontal lobe encephalomalacia, in keeping with the patient’s known prior infarct (Figure 1). 3D time-of-flight MR image demonstrated absent signal of the right ICA and MCA (Figure 2). Frontal view digital subtraction angiography (DSA) of the left ICA demonstrated vessel narrowing at the origin of the left anterior cerebral artery with minimal antegrade flow and compensatory collateral vessels from the left MCA territory (Figure 3A). There was also hypertrophy of the left lenticulostriate vessels (Figure 3B). Frontal and lateral view DSA of the left vertebral artery demonstrated blood flow to the right anterior circulation via the posterior communicating artery and compensatory collateral vessels (Figures 4A and 4B). Frontal view angiogram of the left vertebral artery also revealed a flow-related left posterior cerebral artery aneurysm (Figure 5). In summary, cross-sectional imaging showed hypertrophy of the lenticulostriate arteries, neovascularization, and confirmed the old right MCA territory infarct as well as the chronic right ICA occlusion. Additionally, the patient was found to have a flow-related left posterior cerebral artery aneurysm.

Diagnosis

Moyamoya disease

Discussion

Moyamoya disease (MMD), originally referred to as “hypoplasia of the bilateral internal carotid arteries,”1 is recognized as a nonatherosclerotic and noninflammatory vasculopathy that leads to progressive stenosis of the intracranial ICA and Circle of Willis. The term Moyamoya syndrome (MMS) or Moyamoya pattern is used when these findings are nonidiopathic and associated with various conditions such as vessel wall abnormalities, neurocutaneous syndromes, blood dyscrasias, connective tissue disorders, and even infections.

The characteristic puffy or dense aggregate of branched vasculature visualized in patients with Moyamoya is a compensatory measure stemming from the primary etiological agent of the disease: narrowing or blockage of the intracranial vasculature resulting in reduced blood flow to the brain. This narrowing and occlusive process precipitates proliferation of a network of compensatory collateral vessels, commonly the lenticulostriate and other perforating vessels of the basal ganglia, which is responsible for the smokelike appearance on angiography. The disease progression (on a I-VI grading scale termed the Suzuki scale) is characterized in part by the density of this compensatory network. Common complications of Moyamoya fall into two categories: complications stemming from the initial ischemia (ie, strokes, seizures, etc), and complications stemming from the compensatory mechanisms (ie, hemorrhage).2

CT angiography and MR angiography are the most utilized initial imaging modalities in investigating the anatomical features of MMD and can identify steno-occlusive progression as well as the formation of collateral vessels.3 The gold standard examination to confirm MMD is DSA, which allows visualization of the characteristic dynamic vascular changes. DSA also provides information for staging and consequent risks of the disease using established systems such as the Suzuki classification. The functional features of MMD are examined using perfusion MRI or CT, SPECT, and/or PET scan by assessing cerebral blood flow and cerebrovascular reserve capacity.3

The first official review article on MMD was published in the journal Stroke in 1983.4 There had been 100 reported cases between 1961 and 1980 which highlighted the striking differences in pediatric vs adult clinical and radiologic presentations. Moyamoya exhibits a striking bimodal trend for age distribution, with symptoms most commonly presenting either in children under age 10 or adults aged 30 to 50.4

While the progression of the disease is the same for adults and children, the incidence of symptoms has been found to differ. Analyses of pediatric and adult Moyamoya have found that while ischemic symptoms present at roughly similar rates for children and adults, hemorrhaging is seven times more common for adults than children. Other symptoms stemming from the breakdown of compensatory blood vessels, such as aneurysms and arteriovenous malformations, show similarly uneven incidence among adults and children.

In addition to the vascular symptoms of MMD, the neuropsychiatric symptoms of the condition that have conventionally been attributed to chronic hypoperfusion and/or stroke have also been noted and researched.5 This cognitive dysfunction predominantly manifests in the form of delayed or impaired intelligence in children and as executive dysfunction for adults with MMD.

Although there remains no cure for Moyamoya, many interventions have been developed for management of complications. Most common among these are surgical interventions, although medical interventions such as administration of antiplatelet or anticoagulation agents to prevent ischemic complications are used when surgery is deemed too risky.6 Surgical interventions/bypass are divided into direct or indirect: direct interventions directly connect the external carotid artery to a cortical artery, while indirect interventions involve placement of vascularized tissue supplied by the carotid artery in contact with the brain to induce new vascularization. The direct intervention or bypass is often the more favored option for patients, regardless of age, who have a suitable donor artery.

In conclusion, whether it be idiopathic or part of a syndrome, Moyamoya is primarily managed through symptomatic and preventative treatment. While curative treatment is yet to be available, there are key surgical interventions that are effective for both MMD and MMS.

— Lyle Suh, BS, is a medical student at the University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School in Worcester, Massachusetts.

— Ajit S. Puri, MD, is a professor in the division of neurointerventional radiology in the department of radiology at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center in Worcester, Massachusetts.

— Anna Luisa Kuhn, MD, PhD, is an associate professor in the division of neurointerventional radiology in the department of radiology at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center.

References

1. Kudo T. Spontaneous occlusion of the circle of Willis. A disease apparently confined to Japanese. Neurology. 1968;18(5):485-496.

2. Smith JL. Understanding and treating moyamoya disease in children. Neurosurg Focus. 2009;26(4):E4.

3. Shang S, Zhou D, Ya J, et al. Progress in Moyamoya disease. Neurosurg Rev. 2020;43(2):371-382.

4. Suzuki J, Kodama N. Moyamoya disease—a review. Stroke. 1983;14(1):104-109.

5. Oakley CI, Lanzino G, Klaas JP. Neuropsychiatric symptoms of Moyamoya disease: considerations for the clinician. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2024;20:663-669.

6. Berry JA, Cortez V, Toor H, Saini H, Siddiqi J. Moyamoya: an update and review. Cureus. 2020;12(10):e10994.