September 2013

September 2013

Partner Compensation — Changing Radiology Practice May Call for Changing Income Division Strategy

By Jim Knaub

Radiology Today

Vol. 14 No. 9 P. 16

The business of radiology has grown more complex, so it’s hardly a surprise that radiologist compensation would follow suit.

As radiology becomes more subspecialized, the typical workday of one radiologist can be very different than that of his or her colleagues. An interventional radiologist handling procedures, a breast imager plowing through mammograms, and a neuroradiologist reading MRI exams can be busy all day but show significantly different production in terms of relative value units (RVUs) or revenue production. Yet a radiology group needs all of those components and more to provide full service to a hospital. When dividing revenue, private practice radiology groups face the challenge of equitably balancing radiologists’ individual productivity and their different roles against the services that the entire group must provide to obtain and keep contracts.

Radiology Today spoke with three medical business consultants who have experience with radiology groups to find out what changes in partner-level income division they are seeing in their work. They all noted that radiology groups are more likely to gravitate toward equal revenue sharing among partners compared with other specialties.

“If the partners all share pretty much the same shifts and work, equal shares work pretty well if everyone takes the full rotation,” says Jeffrey B. Milburn, MBA, CMPE, of Colorado-based MGMA Health Care Consulting Group. “It starts to break down when you have people who inherently work harder than others.” And when you mix in imaging’s increasing subspecialization and some partners’ desire to work less than a full-time schedule, those differences can create discontent and instability. “Unless everyone can do everything [and does], to recruit and retain good physicians you have to have some differentiation,” he adds.

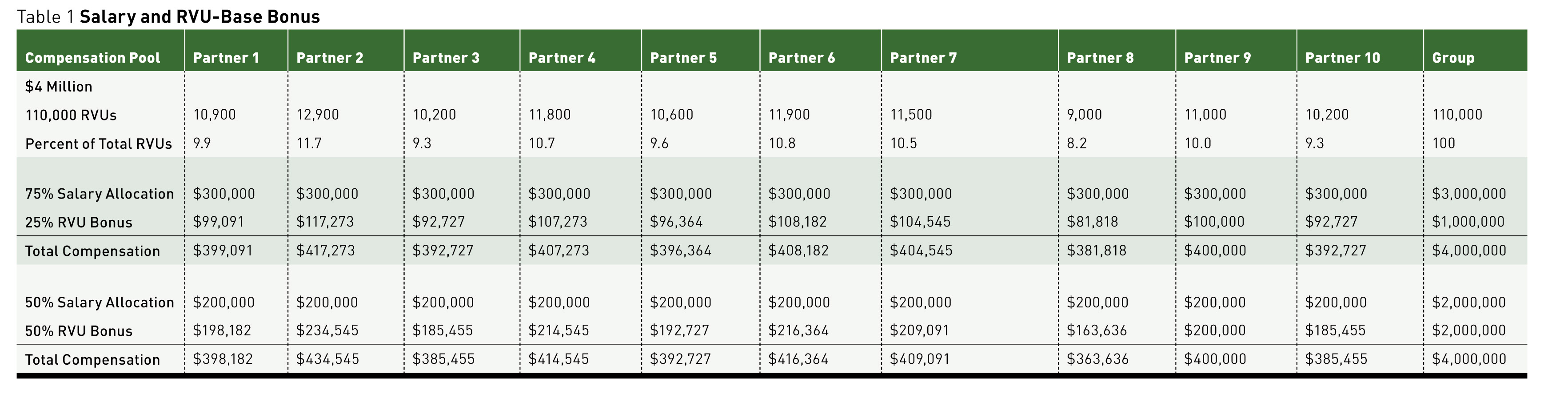

Milburn typically counsels groups to establish a two-pronged structure for partner pay combining a base salary and an RVU-based bonus plan. Each group must work out its own formula, he cautions, but compensation based on 50% to 75% of base salary and the balance based on RVU production is a reasonable range to start the partners’ discussion. He prefers using RVUs rather than revenue measures because it removes the payer mix from the productivity equation. Table 1 (on page ••) shows examples using a 10-partner group sharing $4 million through salary and RVU-based bonuses.

Equal-Sharing Tendency

Health care consultant and attorney Mark E. Kropiewnicki, JD, LLM, still sees a proclivity toward equal-share arrangements among radiology partners but thinks there needs to be some adjustment. “Many are still equal-share arrangements,” says Kropiewnicki, who also is a principal consultant, the president of The Health Care Group, and the president of Health Care Law Associates based in Plymouth Meeting, Pennsylvania. “The problem is they don’t want to rock the boat.”

When a radiology group is reluctant to move away from sharing the reimbursement pool equally, Kropiewnicki will suggest a salary and bonus arrangement that still leans toward equal shares but reduces the bonus to very low producers or provides an extra bonus to very high producers. He says that in most private practice groups, 70% to 80% of the partners’ production is similar. For those radiologists, most seem content with equal sharing, perhaps because they understand that different components of a full-service practice may produce differently but are all necessary for the entire group to succeed.

While this acceptance may be greater in radiology than in other specialties, that sense is not unlimited. At some point, there will be resentment toward a partner who does not pull his or her weight in the group. Likewise, there may be resentment from very high producers who feel they are being undercompensated for their contribution. To protect against both, a group may decide to share the bonus equally unless a partner fails to meet some agreed-upon minimal production level or exceeds some threshold above the group’s average production.

For instance, if a group of 10 partners anticipates a $4 million pool to distribute among those partners, they may budget and pay $3 million in regular salary and project a $1 million bonus pool they intend to share equally, presuming the partners produce relatively equally. Respecting the idea that certain exams and procedures reimburse better than others but all contribute to the practice’s overall success, the partners may decide that all partners within 15% of the group’s mean production (over or under) can share equally in the bonus pool. Physicians who produce 15% less than the mean will see some reduction in their bonus, while those who outproduce the mean by more than 15% will receive an extra bonus.

Each group needs to determine at what levels any penalties and extra bonuses will kick in and how to calculate those amounts. Kropiewnicki says he’s seen groups settle on a threshold of 10% to 20% above or below mean production. “Most radiology groups think in terms of ‘We, collectively, have to get the job done,’” he says. “The problem can be how to measure that everyone is working as hard as they can.”

Having a defined way to handle a physician who may not produce to the standard of his or her colleagues provides some group protection and makes it easier to deal with this kind of problem partner. Kropiewnicki also notes that as groups become larger, they tend to become more subspecialized, which also can lead to variability in partner production.

RVUs and Shifts

Daniel Corbett, a consultant and the director of business development for Radiology Business Solutions (RBS) in Flint, Michigan, sees radiology becoming increasingly complex both in terms of radiologist work patterns and reimbursement changes, accelerated by the Affordable Care Act. Corbett believes radiology groups’ partner compensation needs to account for that complexity.

With some clients, Corbett has implemented a two-tiered plan based on RVUs produced and shifts worked. The process starts with the group defining an expected amount of work a radiologist should be able to handle on a given shift. Corbett says most groups settle on a spot between 40 and 50 RVUs per shift as the group’s expected production. Using that projected production, the group determines the appropriate compensation per shift.

Because some work shifts are less desirable than others, compensation per shift is weighted to reflect that. For example, a weekday day shift could be weighted as one shift, while a weekday evening is compensated as 1.2 and a weekday overnight as 1.5. Weekend shifts are compensated as 2 shifts. Once all the shifts are defined, the partners select shifts in turns like a fantasy football draft.

Corbett recommends that the groups also create rules defining the number of vacation weeks, typically a minimum of eight and a maximum of 14 weeks. He suggests using the draft to set schedules for the entire year, or at least six months. He says that when the relative shift values are properly balanced in the group’s view, the incentives to earn more money for taking unpopular or extra shifts also tend to balance out. Radiologists wanting or needing to earn more pick up less desirable and extra shifts from those happy to work less. That shift-based component comprises 40% to 60% of partner pay.

The remaining piece of RBS’ income pie is based on RVU production, with an interesting disincentive for cherry-picking the worklist. If the group decides that 46 RVUs is the expected daily production, any RVUs over 50 reduced in value for RVU compensation purposes. He says creating a point of diminishing return for cherry-picking incents partners to simply read the next exam. Also, structuring reimbursement based on a reasonable day’s work can support quality because there’s less incentive to read too fast in order to earn more.

“It really engages the doctors to look at the system,” Corbett says. “If everyone wants the afternoon shift and no one is trading, you’re paying too much for that shift. You have the right balance when radiologists are only making changes for vacation and family reasons.”

Corbett admits the system is complex, but he believes it is flexible and can be tweaked to address a group’s individual needs to account for shift differential, part-time partners, and reduced call.

Milburn agrees with the need to adjust compensation for different situations. He says paying radiologists additional money for night and weekend call is necessary if such coverage isn’t shared equally, and that some productivity compensation also helps a group recruit and retain good radiologists.

Part-Time Partners?

Partners who want to work less than full time can create problems in a group. In the short term, compensation for a partner taking a maternity leave, sabbatical, or health-related leave of absence is pretty straightforward. Based on the group’s agreed-upon policy, compensation can be temporarily adjusted in the short term based on the understanding that the partner intends to remain a full participant in the group over the long term. If the terms of such leaves are fair and spelled out by the group, they essentially become a perk of being a partner and more a matter of group governance than income division.

The situations where a partner wants to scale back his or her workload as a transition to retirement or generally work less than full time, such as a parent who wants to be home when his or her children come home from school, can be more complicated. The financial component of being a part-time partner can be handled easily enough. In an equal sharing group, a partner’s share would be prorated based on the percentage of a full schedule worked. In a plan split between base salary and production, the salary portion would be prorated and an RVU- or revenue-based bonus would adjust based on reduced production. The trickier parts of compensation for part-time partners are benefits and governance issues, such as partner voting rights.

Kropiewnicki believes the full-time partners must be the primary consideration of a successful group. Too much accommodation for part-time partners risks the tail wagging the dog. He generally recommends straight salary compensation for partners working part time, with the main exception of an agreed-upon procedure and time frame for partners who want to scale back as they approach retirement. Kropiewnicki believes partners who reach a certain age and number of years of service to a group can be permitted to work less—perhaps four or three days per week—scaling back to half time over their last years with a group.

Reducing night call is a common desire for radiologists approaching retirement. Kropiewnicki recommends establishing a monetary value for a call shift and reducing the partner’s compensation by that amount for not taking his or her share of call duty.

The key, he says, is defining the terms and time frame. A group may allow scaling back over five years, with an agreed-upon end date. At the end of that defined period, the partner then officially retires and is bought out of the practice in accordance with the group’s agreed-upon terms. Benefits and voting privileges of part-time partners also need to be defined.

“When you decide to pull that retirement trigger, you have a defined number of years and then you’re no longer a partner,” Kropiewnicki says. “The group and the doctor might then agree to hire the doctor as a part-time employee.”

Kropiewnicki’s intent is to protect the larger group as an ongoing entity. He also notes that such a prelude to retirement is easier to accommodate in a larger radiology group because the reduction in one person’s contribution creates less disruption. A 20-partner group with two radiologists shifting into retirement is affected less dramatically than a five-partner group with two members scaling back.

Ideally, a system for retiring partners will be in place before it’s needed, but Kropiewnicki says that situation often is not considered until someone in the group wants to work less.

Corbett’s approach of paying by shifts and RVUs accommodates the pay side of part-time work, so the group just needs to establish its rules governing reduced participation. Corbett says RBS typically recommends when a radiologist transitions to a part-time status, the ability and terms of participation in benefit programs are carefully weighted, and sometimes the cost of participation is shifted more heavily to the radiologist as a measure of fairness. In a large group run by a board of directors, the group also would need to decide whether only full-time partners could serve on the board.

Leadership

Compensation for leadership duties is another income-division issue. A surprising number of groups don’t compensate a leader physician at all, expecting that person to perform those duties in addition to a full share of the work. The advisors interviewed for this article think it’s best to find some way to compensate physicians for the time spent in important nonclinical activities that help the group get and keep its contracts.

In groups sharing income evenly, the matter can be as simple as allowing a physician the time outside of the reading room during a shift to perform those duties while still receiving a full-income share. Corbett’s approach based on shifts and RVUs can accommodate important leadership activity by having the group assign an RVU value to include in both shift and RVU bonus portions of the income formula. For example, using 46 RVUs per shift in the example described earlier in this article, it would be easy enough to estimate a value and plug it into a calculation. If a physician needs two hours to attend a hospital board meeting, he could be credited with 9.2 RVUs of production even though he or she misses two hours of a 10-hour shift.

New Wrinkle: Accountable Care Organizations

While accountable care organizations are not yet a prominent feature on the health care landscape, that doesn’t mean forward-looking groups should not be thinking about them in terms of income division. That means considering how to begin incorporating quality measures and outcomes in partner compensation.

“If the payer isn’t demanding it, come up with your own measures,” Milburn says. “This is coming one way or another. Get the doctors used to it. It’s also good marketing.”

In a private practice setting, Milburn suggests allocating maybe 5% of the group’s bonus pool to be paid on some group-defined quality or outcomes measures, including patient satisfaction. He suggests that a group should create up to five measures to incentivize with the carveout. And they shouldn’t make the standard excessively high to start—perhaps meeting three of five measures. The point is to start physicians thinking about measuring quality and incenting desired behavior, not to create animosity toward quality measures.

Milburn also mentioned that a large number of radiologists are affiliated in some way with integrated delivery systems. He says these organizations tend to be ahead of private practice in this area. He says as much as 20% of income could be based on quality, outcomes, and patient satisfaction in just a few years in those settings.

Take-Home Message

The take-home message is that radiology is changing, and radiologist compensation probably needs to reflect that.

“When you implement something new, it can be difficult,” Corbett says. “It takes a strong leader to power through that. Sometimes it’s easier for bigger groups to change because they’re run by a board, but those middle-sized groups—between six and 15 radiologists—are usually the ones that most need to think about this.”

— Jim Knaub is editor of Radiology Today.

(Click to enlarge image.)